The Sutton Hoo Ship.

History, Egyptian Nile barges, Greek triremes, Roman Galleys, Viking longships. That’s the sequence, right?

8th June 793, Scandinavian pirates sacked the monastery of St. Cuthbert on the island of Lindisfarne. Alcuin, a Northumbrian scholar monk, wrote about it “Never before has such terror been seen in Britain as we have suffered by these pagan people, nor was such a voyage thought possible.” That was the beginning of the Viking period of North European history and it was all down to the longships. In the museum at Oslow there’s the beautiful Gokstadt ship to prove it.

Not so fast!

The Romans conquered Britain in 43 a.d. and left around 410 a.d. and the dark ages descended on Britain, till the Norman Conquest in 1066 and the Middle Ages began. Somewhere between the Romans and the Vikings might have been Arthur and Camelot, Arthur doesn’t seem to have been a fan of Anglo-Saxons. What we knew of the period used to be from a book by a monk called Bede, who wrote “Ecclesiastical history of the English People” in Northumbria sometime in the early 700s. He died in 753 a.d. Naturally enough, his history was mainly concerned with the spread of Christianity in Britain, and he wasn’t too fond of pagan Anglo-Saxons either. (Alcuin was a pupil of Bede). After the Vikings started being nasty, Anglo-Saxons got Christianity and turned into the good guys under Alfred the Great, who resisted the Viking invasion.

Well, it’s actually all a bit more complicated than that, and one of the major reasons for looking again at that 600 years of history is a hole in the ground at a place called Sutton Hoo, near Woodbridge in Suffolk, England, around 20 minutes drive from where my parents used to live.

Sutton Hoo overlooks the river Deben, and at the top of the slope were a series of mounds. In 1938 the owner of the estate, a Mrs Pretty, decided to excavate some of the mounds, under the supervision of Mr. Basil Brown, and with the encouragement of the local Ipswich museum. The following year Basil Brown found this:

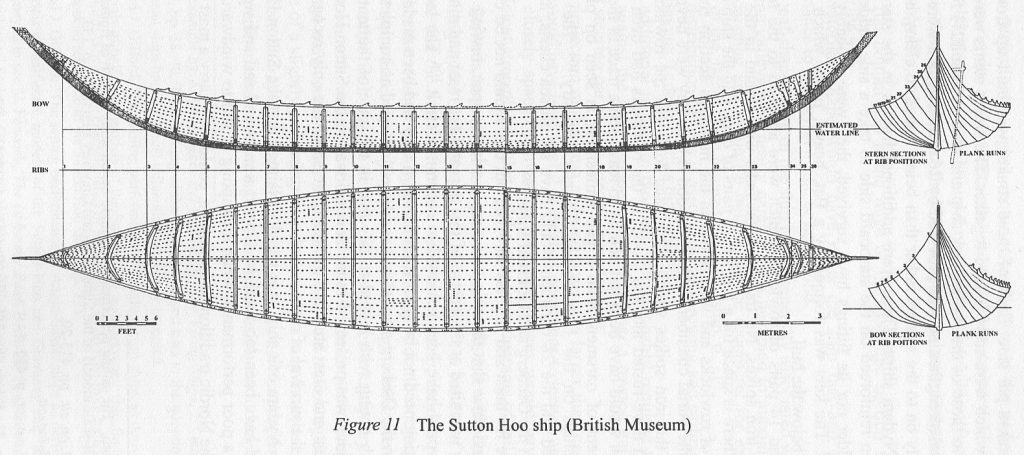

What you are looking at is stain marks in the very sandy soil. The wood had long since rotted away, but the rust and rust stains from the iron clench nails were very clear. The ship was about 89 feet long, 14 feet wide, and 4 1/2 feet deep. These are the lines:

In the centre of the ship was a burial of an obviously rich and important man. There was just time to recover the burial objects and get them to the British Museum before the work was rudely interrupted by a German chap, and the site had to be back-filled and left alone for five years.

Nowadays there’s a very nice museum on the site, Mrs. Pretty donated the whole of it to the nation, and you can walk around the mounds and get a sense of the landscape and the history.

The story I want to tell is about the ship, and the way it pushes the view of history.

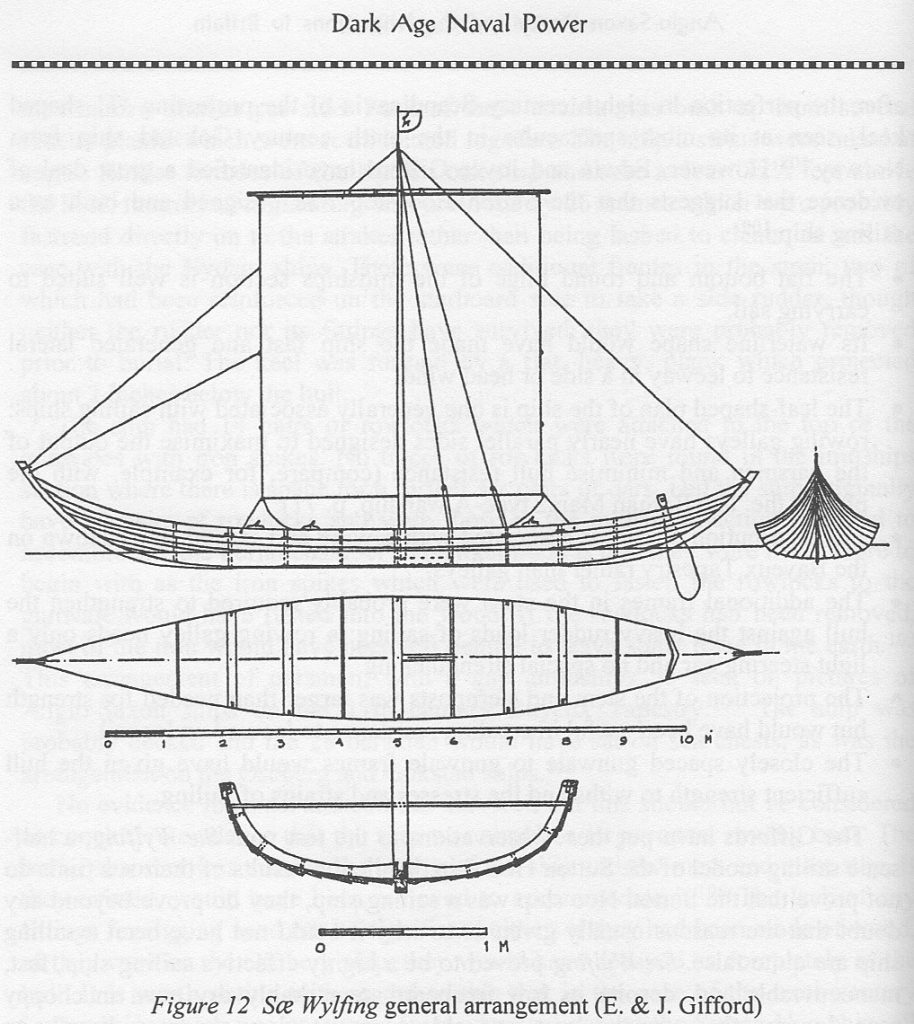

In 1993 a half size replica of the Sutton Hoo ship was built, the Sae Wylfing, and sea trials were later carried out both rowing and sailing. The trials proved that the original ship could easily reach 10 knots under sail, with a possible maximum of 12 knots. In calm seas it could have made progress upwind under sail at about 1.5 knots and could have held its station against the wind under more adverse conditions. It probably had 14 oars on each side so it had about 6 horsepower available from the crew.

From the mouth of the River Deben, the Hook of Holland (the mouth of the Rhine) is due east and 102 nautical miles. On a really favourable summer’s day, the owner of this ship could have an early breakfast in Angleland, and be getting stinking drunk in Germania before bed.

This ship was buried about 625 a.d. There are signs of repairs so it was likely well used and built sometime around 600 to 610. The most likely person it contained was an Anglo-Saxon king by the name of Raedwald, who allowed both pagan and christian worship in his time. We are looking at a ship ten feet longer than the Gokstad ship, and built 250 years before it!

The burial was rich, the most magnificent helmet/face mask I know of, wonderful Anglo-saxon gold jewelry and iron craftsmanship, and coins from as far away as Syria, yes Syria! You can google all this!

Here comes the complication, bear with me!

Let’s try to get back to the beginning of the Anglo-Saxon story in Britain. The Roman author Tacitus, writing about 100 a.d. tells a story from 83 a.d. about a cohort of “Usipi” serving under Agricola on the West coast of Britain. The Usipi were a tribal group from the middle Rhine, near modern day Cologne. This cohort killed their officers and siezed three Liburnian galleys of the Roman fleet, sailed the galleys around the North of Scotland, pillaging as they went, crossed the North Sea, and eventually came to a bad end, shipwrecked on the Danish/German coast, presumably trying for the Rhine. They were taken as pirates by the Frisians, (think northern Holland and north-west Germany) and either killed or sold back into the Roman Empire to the south as slaves. Tacitus presumably got the story from the slaves.

The Liburnian galleys were the “standard ship” of the Roman Empire in the first and second centuries. They were lightweight and fast, usually with double banked oars in the Mediterranean but in Britain they probably had a single bank of oars and a single square sail. The rougher seas of the Atlantic would make biremes much less effective. Some time after this mutiny, Agricola also ordered a Roman fleet to circumnavigate Britain, and they succeeded. To go from a Liburnian galley to a ship like the one at Sutton Hoo, the construction method is changed from carvel to clinker, which also takes you from a straight-sided hull to a more leaf shape, which is lighter and a better boat under sail.

Clinker construction dates back at least to the Hjortspring boat from Als in southern Denmark. This was buried in a peat bog around 350 b.c. 400 years before the Romans came to Britain.

It was typical of the Roman occupation of Britain that the legions’ infantry and officers were Romans, but the auxiliaries, cavalry, engineers, scouts and skirmishers, were recruited in Europe, mostly from Germanic tribes.

And the Legion offered a great career, for most of its 400 years Roman Britain was a peaceful and prosperous place, and the Legions main work was engineering, straight Roman roads, permanent camps and barracks, and of course great fortifications like Hadrian’s wall. And 20 years service in the Legions could get you a land grant in the occupied lands, as well as a skilled trade. Colchester, only some 20 miles from Sutton Hoo, was the great classic example of a Roman legion headquarters.

In the North Sea, though, the Romans had a piracy problem from tribes in Scandinavia and those in what is now northern Holland and Germany. These pirates raided all the way through the channel and along the coast of northern France, as well as occasional raids in Britain. They were active for the whole four centuries, but with the Legions well organized and good roads, Britain was a tough nut for pirates to try to crack.

The Romans maintained two fleets with responsibilities in the North sea and the English channel, the Classis Germanica, based on the Rhine, and the Classis Britannica, based on the eastern and southern shores of Britain. The Classis Britannica did have some anti-piracy role, but it’s main purpose was logistical support of the legions in Britain, carrying supplies and personnel. I haven’t yet found a reference as to whether these fleets were manned exclusively with Romans, but it is certain that at least the builders and maintainers of the ships would have been classed as Auxiliaries, and used any skilled craftsmen they could get hold of.

So the Roman occupation of Britain included large numbers of disciplined, skilled men of Germanic origin, familiar with the English channel and the North sea, and capable of building and sailing seaworthy craft.

From these threads, I weave my current view of the history of East Anglia, the big bulge to the East and North of London, in this way.

By the time the Romans left Britain, I believe large areas of East Anglia had been farmed and owned by German ex-legionaries and their children for a couple of hundred years. The original British Celtic inhabitants must have felt about the legions much as the British felt about American forces in the Second World War, “Over-paid, over-sexed, and over here!”. But their grandchildren would likely be part Germanic. And you can be sure that a Saxon master craftsman would pass on his craft and the organization of it to his sons and grandsons. And these men had the ships and the skills to get to the Rhineland and Normandy and back in less than a week. That’s less than the time you could get to London and back by land.

So its not really a surprise that two hundred years later, the local ruler was brought up to worship German gods, was very rich, commanded craftsmanship that takes years of organized apprenticeship to learn, and owned a ship as big and as fast as anything else on the North Sea. He had trade links that brought him coins all the way from Syria, and his people thought enough of him to give him a spectacular funeral.

We learned our history of the post-roman period in Britain from Celtic christian monks, and from the mythical stories of Arthur, fighting to resist the Anglo-saxon invasion! Until the Anglo-saxons became Christian, theirs was a society without written records. And no Icelanders ever wrote down the Anglo-Saxon skalds stories. The only competition to the Venerable Bede is the epic poem Beowulf, which tells nothing of actual history, but much about what they liked to listen to in a feast hall.

So we got this idea of the Dark Ages, savage, chaotic, and primitive, everyone living in mud huts, lives short, nasty, and brutish, but it doesn’t seem to me to fit the facts of craftsmanship, prosperity, and communications that are proved by the Sutton Hoo burial.

I think the Anglo-Saxon invasion was less a series of savage military campaigns than it was a matter of cousins arriving by invitation to help on the farms and the factories and, in the off season, raiding prosperous but poorly defended inland areas. Naturally, rule over an area was up for grabs by whoever could organize a temporary ascendancy. In East Anglia, I believe the majority of the period was relatively peaceful, led by no-nonsense burghers with a culture of discipline and skills derived from the auxiliaries of the Roman Empire. Farming flourished on the good land, trade with Europe was easy and prosperous, and craftsmanship and practical skills were highly valued. Communication up and down the east coast of Britain and across the North sea and the Channel was easy and fast, the sea was a rich source of food, and I am certain that the whole North sea was busy with clinker built boats large and small.

This one ship, just a set of rust stains in the sand, beats down the structure of the history I was taught as a child, and all the assumptions that it made about what a pagan culture without written records could achieve.

The idea of modelling it, and learning to sail it with a single square sail, “like a worm i’the bud, feeds on my damask cheek”.

References: The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial, R.L.S Bruce-Mitford, British Museum.

Dark Age Naval Power, John Haywood, Anglo-Saxon Books.